import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from feynman import Diagram

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(9, 3), frameon=False, tight_layout=True)

fig.patch.set_visible(False)

for a in ax:

a.axis("off")

a.set_xlim(0, 1)

a.set_ylim(0, 0.8)

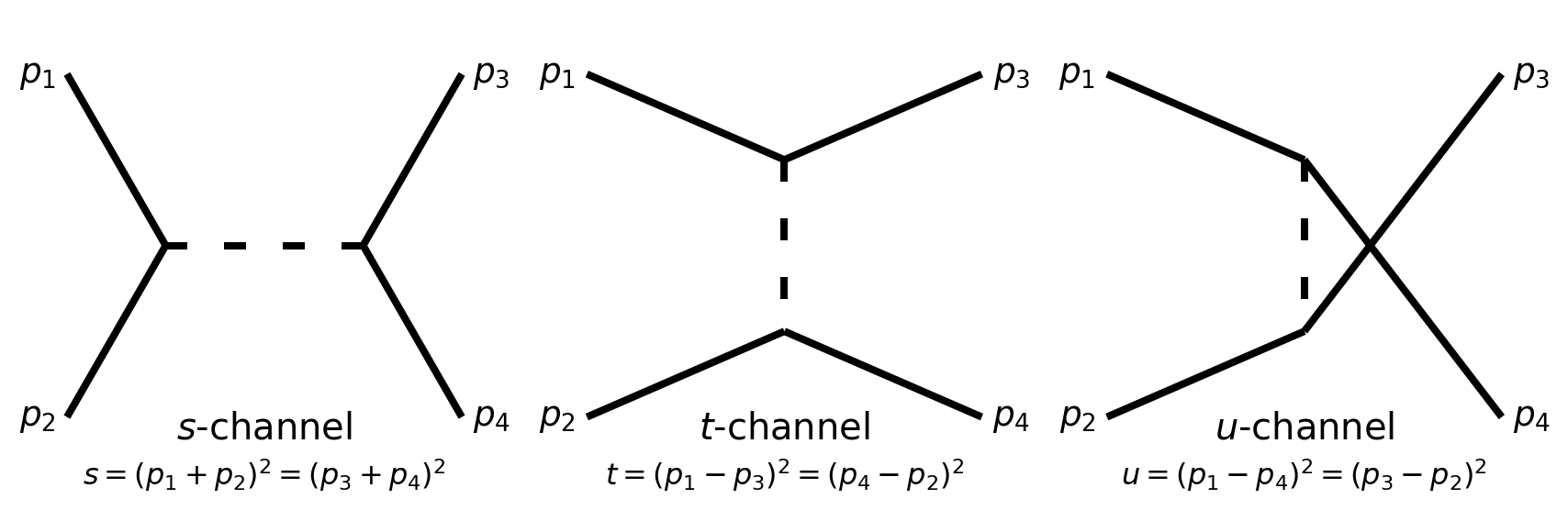

s_channel = Diagram(ax[0])

# Vertices

v_p1 = s_channel.vertex(xy=(0.1, 0.7), marker="")

v_p2 = s_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dy=-0.6, marker="")

v_p3 = s_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dx=0.8, marker="")

v_p4 = s_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p3.xy), dy=-0.6, marker="")

v1 = s_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dx=0.2, dy=-0.3, marker="")

v2 = s_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p3.xy), dx=-0.2, dy=-0.3, marker="")

# Lines

p1 = s_channel.line(v_p1, v1, arrow=False)

p2 = s_channel.line(v1, v_p2, arrow=False)

interaction = s_channel.line(v1, v2, style="dotted", arrow=False)

e4 = s_channel.line(v2, v_p3, arrow=False)

e5 = s_channel.line(v_p4, v2, arrow=False)

# Labels

v_p1.text("$p_1$", x=-0.06, y=0)

v_p2.text("$p_2$", x=-0.06, y=0)

v_p3.text("$p_3$", x=+0.06, y=0)

v_p4.text("$p_4$", x=+0.06, y=0)

s_channel.text(0.5, 0.08, "$s$-channel", fontsize=15)

s_channel.text(0.5, 0, "$s = (p_1 + p_2)^2 = (p_3 + p_4)^2$", fontsize=12)

s_channel.plot()

t_channel = Diagram(ax[1])

# Vertices

v_p1 = t_channel.vertex(xy=(0.1, 0.7), marker="")

v_p2 = t_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dy=-0.6, marker="")

v_p3 = t_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dx=0.8, marker="")

v_p4 = t_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p3.xy), dy=-0.6, marker="")

v1 = t_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dx=0.4, dy=-0.15, marker="")

v2 = t_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p2.xy), dx=0.4, dy=+0.15, marker="")

# Lines

p1 = t_channel.line(v_p1, v1, arrow=False)

p2 = t_channel.line(v1, v_p3, arrow=False)

interaction = t_channel.line(v1, v2, style="dotted", arrow=False)

e4 = t_channel.line(v2, v_p2, arrow=False)

e5 = t_channel.line(v_p4, v2, arrow=False)

# Labels

v_p1.text("$p_1$", x=-0.06, y=0)

v_p2.text("$p_2$", x=-0.06, y=0)

v_p3.text("$p_3$", x=+0.06, y=0)

v_p4.text("$p_4$", x=+0.06, y=0)

t_channel.text(0.5, 0.08, "$t$-channel", fontsize=15)

t_channel.text(0.5, 0, "$t = (p_1 - p_3)^2 = (p_4 - p_2)^2$", fontsize=12)

t_channel.plot()

u_channel = Diagram(ax[2])

# Vertices

v_p1 = u_channel.vertex(xy=(0.1, 0.7), marker="")

v_p2 = u_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dy=-0.6, marker="")

v_p3 = u_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dx=0.8, marker="")

v_p4 = u_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p3.xy), dy=-0.6, marker="")

v1 = u_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p1.xy), dx=0.4, dy=-0.15, marker="")

v2 = u_channel.vertex(tuple(v_p2.xy), dx=0.4, dy=+0.15, marker="")

# Lines

p1 = u_channel.line(v_p1, v1, arrow=False)

p2 = u_channel.line(v1, v_p4, arrow=False)

interaction = u_channel.line(v1, v2, style="dotted", arrow=False)

e4 = u_channel.line(v2, v_p2, arrow=False)

e5 = u_channel.line(v_p3, v2, arrow=False)

# Labels

v_p1.text("$p_1$", x=-0.06, y=0)

v_p2.text("$p_2$", x=-0.06, y=0)

v_p3.text("$p_3$", x=+0.06, y=0)

v_p4.text("$p_4$", x=+0.06, y=0)

u_channel.text(0.5, 0.08, "$u$-channel", fontsize=15)

u_channel.text(0.5, 0, "$u = (p_1 - p_4)^2 = (p_3 - p_2)^2$", fontsize=12)

u_channel.plot();